• In the previous post I wrote about ‘research’ which seeks to provide support for state intervention.

A more recent spin on this theme is work that tries to show that critics of intervention, or those who fail to demonstrate allegiance to the prevailing ideology, are excessively anxious, or otherwise psychologically odd. It is rather like a tobacco company pumping out research which supposedly shows (a) that smoking is not bad for you, and (b) that critics of tobacco are psychotic.4 days after posting this came news that academics at San Diego and Harvard claim to have demonstrated a gene-based link between (a) voting for people like Al Gore or Barack Obama, (b) “openness”, and (c) sociability.

a variant of a gene called DRD4 makes people more likely to be liberal, if they also had many friends as teenagers. Appearing in the current edition of The Journal of Politics, the research ... found that people with a specific variant of DRD4 were more likely to be liberal as adults, but only if they had an active social life in adolescence ... [The researchers] hypothesized that people with the novelty-seeking gene variant would be more interested in learning about their friends’ points of view. Thus, they might be exposed to a wider variety of social norms and lifestyles, which could foster a liberal viewpoint.I am surprised the researchers did not also find that liberals (i.e. leftists) are kinder to puppies, and more likely to help old ladies cross the street.

• The paper (in JOP 72, pp.1189-1198) explains that

• The paper (in JOP 72, pp.1189-1198) explains thatCertain situational and dispositional factors may contribute to a cognitive-motivational orientation toward the social world that is either closed and invariant or open and exploratory. In fact, “openness to experience”, a construct conceptually related to novelty seeking, is the personality trait most commonly linked to political orientations ... and has been found to be negatively related to political conservatism generally ... and sociocultural conservatism specifically.I wonder whether the whole leftists-are-openminded ‘research’ programme might not unravel if one deconstructed some of its underlying assumptions. If, for example, the personality questionnaire purporting to measure “openness to experience” does so by enquiring about the subject’s interest in variety and change, then

– (a) there would be a potential conflation of two distinct characteristics, (i) being open to different things and (ii) seeking variety, or wanting change;

– (b) the research could be picking up on a link between liking change, and voting for parties that are more likely to promise change, a link which would be neither surprising nor very informative, and which would not necessarily have much to do with open-mindedness in the usual sense of that word.

Incidentally, it would be unfair to judge the current issue of the Journal of Politics by its cover without reading the articles, but looking at the contents it is hard to avoid the impression that the average position of the contributors is well to the left of political neutrality. I wonder if there is not something a little absurd in having an academic subject, supposedly concerned with the study of politics, that has its own political position, which furthermore bears little relation to the average position of the current population — let alone a more general 'average' political viewpoint, taking a somewhat broader historical perspective.

• Also in the previous post I wrote about the tendency for people to react ‘personally’ to ideas.

Instead of considering whether something is true, people ask themselves, “how does this affect me? should I have an emotional reaction to this?”A week or so later, Mr Stephen Fry attracted attention with the remark, made during an interview, that the only reason women have sex with men

is that sex is the price they are willing to pay for a relationship with a man, which is what they want ... Of course a lot of women will deny this and say, ‘Oh, no, but I love sex, I love it!’ But do they go around having it the way that gay men do?The result — a minor media storm — was illuminating, and consistent with my hypothesis. Reactions were of the type:

– “Well, we all know why you think that, don’t we.”

– “As a woman, I feel offended and outraged. How dare he?”

– “I have always enormously enjoyed sex with every one of my many, many boyfriends, thank you very much!”

– “I suppose Stephen Fry thinks women should go back into the kitchen where they belong!”

Perhaps Mr Fry’s suggestion deserved a slightly more considered hearing. It may be incorrect, applied to the average woman, but on the other hand perhaps there is something in it.

I suppose that it takes a gay man to even tentatively propose such a thing. Imagine if a heterosexual male were to do so. He might end up in fear for his life, and would certainly end up in fear for his sex life. So perhaps one should acknowledge Mr Fry's contribution to opening a debate on this important topic — although it appears not to have stayed open for very long before ideological enforcers helpfully restored the original, no doubt correct, article of faith.

* * * * *

• For a country that produced and celebrates The Simpsons, a show that manages to insult every nation it touches — the most notable examples being Brazilians and Indians — America can be touchy. A US reader cancelled his feed subscription in response to my August post, apparently because I flippantly referred to his countrymen as “simple indigenous folk”. Getting a sub cancellation makes me feel quite dramatic, a bit like Private Eye.

• For a country that produced and celebrates The Simpsons, a show that manages to insult every nation it touches — the most notable examples being Brazilians and Indians — America can be touchy. A US reader cancelled his feed subscription in response to my August post, apparently because I flippantly referred to his countrymen as “simple indigenous folk”. Getting a sub cancellation makes me feel quite dramatic, a bit like Private Eye.• Dear Private Eye. They were the only member of the Press who responded to invitations to the book's launch party. The person they sent along to the Oxford & Cambridge Club blagged a free copy of the book, in exchange for promising to approach Richard Ingrams about my writing something for The Oldie. I never heard from her again.

• I gather it has become illegal to deal in jokes about people of Irish extraction. The act of asking people to send in Irish jokes, for example, seems to be a potentially imprisonable offence under “incitement” legislation, thanks to the dear Labour Party while in government — the party that claims to represent ‘liberals’. How can a nation that produced Oscar Wilde and Flann O’Brien tolerate this sort of baloney? If I were Irish, I would write to my Teachta Dála to complain.

• Fortunately, it is not yet illegal to be flippant or critical about Americans. I think one should be able to be flippant or critical about major religions, and even about ethnic groups. I tend not to do so myself because I think it is impolite, but I am not a believer in legislating for politeness. Although, if you are going to have laws of this nature, I would start by banning the use of the words “guys” and “enjoy” in restaurants.

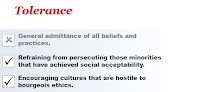

• The ability to be flippant or critical about collections of people may seem trivial. To appreciate its significance you have to turn it around: it is virtually impossible to prohibit flippancy or criticalness in areas where it might seem pointlessly offensive, without encroaching on areas that are not trivial. The rule about not damaging the position of a specific person is a very carefully defined and long-established exception to the basic principle — or, rather, to what was formerly a basic principle.

• At the time the “hate speech” laws were brought in, it was argued (by those wanting them) that they would not be used against comedy, and this argument seems to have been persuasive. How can people be so gullible? “We know that new law X could in theory be used for purpose B, but we promise it never ever will be.” Could the Lib Dem civil liberties team please look into reversing this seriously retrogressive piece of stifledom.

• As for Americans, they seem an odd mixture — though I suppose this could be said about most other countries too. On the one hand, they are now probably the stuffiest nation on earth, apart from the French; our own former pole position having been lost, now that Britain’s image has been successfully inverted. On the other hand, they are probably also the most subversive nation on earth, partly perhaps because they have always had, and still have, a genuinely liberal attitude to culture (outside their universities), unlike the inverted version of liberal which is now practised in Britain and other parts of Europe. For example, they have produced some of the world’s most subversive comedians, including a man who probably deserves the record for most subversive ever. Personally, I find much of his output too disturbing to be funny, but there is little doubt that he was a true original. Deliberately provoking and antagonising one's audience, as a kind of artistic device, and to shake up cognitive complacency? Interesting.

• As for Americans, they seem an odd mixture — though I suppose this could be said about most other countries too. On the one hand, they are now probably the stuffiest nation on earth, apart from the French; our own former pole position having been lost, now that Britain’s image has been successfully inverted. On the other hand, they are probably also the most subversive nation on earth, partly perhaps because they have always had, and still have, a genuinely liberal attitude to culture (outside their universities), unlike the inverted version of liberal which is now practised in Britain and other parts of Europe. For example, they have produced some of the world’s most subversive comedians, including a man who probably deserves the record for most subversive ever. Personally, I find much of his output too disturbing to be funny, but there is little doubt that he was a true original. Deliberately provoking and antagonising one's audience, as a kind of artistic device, and to shake up cognitive complacency? Interesting.* * * * *

• I have seen the argument that it is an overreaction to the recent addition to anti-speech laws to claim it prohibits office jokes. Well, it surely puts a cloud over a lot of them. What proportion of casual humour would you say categorically is of no possible offence to any member of a group with “protected” characteristics? If you have to restrict yourself to the unequivocally safe portion, would it not be simpler just to stop making jokes, or any jocular references, altogether? “People will go on making jokes regardless.” Not a good answer. The response to a silly law may well be for the majority to ignore it. The fact remains that our liberties — and the quality of life of those who mind about them — have been curtailed yet again.

I gather that a dinnerlady was recently accused of falling foul of “grooming” legislation, and found her livelihood threatened, because she responded to a pupil’s request for a biscuit. So it does not seem particularly farfetched that the fear of an action being perceived by the local Personnelkommandant as “related to a protected characteristic” will have effects, if only on people’s background level of comfort.

• I have also seen the argument that being ‘alarmist’ about a change in the law, once it has happened, is counterproductive, because it creates a more anxious and litigious climate than if one had taken a more ‘chilled’ approach. Again, I do not regard this as a sound response. If liberty is being curtailed by a new law, we need to think about the full extent of how that law could be applied in the future. It is not an adequate counterargument to say that the least fallout from a bad thing comes from not making a fuss.

The idea of a “reasonableness test” also provides little consolation. Laws should be clear and transparent, so that every citizen can predict what actions will and will not represent transgressions, without having to guess what state employees will consider “reasonable”.

• Re Fleet Street failing to stand up for free speech. Even when defending something as trivial as the office joke (sadly, not hard enough — such jokes are now passed on, they are no more, they have ceased to be, they are expired and off the twig), journalists cannot resist making the enemy’s arguments for them. The Independent: “Of course we should try to make the workplace fairer. Of course we should try to help people with disabilities, and maybe even some people with peculiar beliefs, to get work”. Translation: “Of course I go along with the basic principle that the collective should seek to tinker with what goes on in civil society, to make it more compatible with the dominant ideology of the moment, using legislation where necessary”.

* * * * *

• How are liberties won? No doubt many causes are involved. But one factor is that those who care about them sound sufficiently persuasive, while those who resist them become sufficiently resigned. How are liberties lost? The same way in reverse: because those who wish to retain them no longer care as much as those who wish to remove them.

• How are liberties won? No doubt many causes are involved. But one factor is that those who care about them sound sufficiently persuasive, while those who resist them become sufficiently resigned. How are liberties lost? The same way in reverse: because those who wish to retain them no longer care as much as those who wish to remove them.The New Labour era can be seen as an illustration of the latter: those who wanted to remove freedoms, allegedly to ‘do good’, managed to sound more urgent and convinced than the defenders of those freedoms. In some cases the freedoms were civil liberties; in others they were financial freedoms which were reduced in order to fund more state interference or ‘services’, though the reduction part of the package was cleverly deferred until after those responsible for the changes had left the building.

• Reader T.J. writes in connection with the previous post:

I agree with your arguments for free speech, but I also think it is important to maintain social norms against such things as making arguments on the basis of flawed evidence, or arguing in bad faith. When the President of Iran denies the Holocaust he is doing it because attacking the Jews is cheap fodder in Iranian politics. When a think tank claims that global warming is a myth, and when that think tank is funded by an oil company, and that oil company stands to benefit from a general belief that global warming is a myth, then it is entirely legitimate to argue that this think tank shouldn't be taken seriously. One might even be wrong to argue that the think tank shouldn't be taken seriously, the think tank might have some valid contribution, but the fact that they're taking money from an oil company (and that an oil company is prepared to give them money) is still a worthwhile thing to consider.T. is alluding to an issue distinct from that of free speech: how much notice should be taken of views which seem to conflict with prevailing standards of rationality, or where there seems to be an axe to grind; and, more importantly, should such views receive funding or other forms of support? The issue is distinct, but there is an obvious connection to free-speech legislation: the more it is seen as acceptable to dismiss an idea as absurd, the less resistance there is to outlawing its expression altogether.

Imputing dodgy motivation, and dismissing someone’s viewpoint on that basis, is something which perhaps is ideally avoided. I do not agree with those who claim that impartiality is impossible, or nonsensical, but it could be argued that no one is free from potential bias, so using T.’s approach would tend to negate the possibility of rationality altogether. If one is going to be cynical about a think tank supported by oil companies, then one should probably be equally cynical about academics funded by the government. How likely is it that the machinery of a state which absorbs half of national output, and which has the automatic expansionist tendencies of any organisation, will fund research which might suggest that it would be better if there were less state activity?

As for the consensus at any given time about what is beyond the boundaries of reasonable debate, history suggests that one should be wary of regarding this as a reliable guide.

• T.J. sounds dubious about my claim that the tendency for people to react personally is on the rise.

I take the point about emotivism. I suspect that this isn't a 'new' problem. This is the way of the world. People sometimes get offended because they identify themselves with their political/moral beliefs quite strongly. I wouldn't worry too much about it.Unfortunately, what T. calls “emotivism” does not stop with emotions these days, but is turned into anti-speech activism. Not only does a mediocracy encourage people to react personally, it incites them to turn their emotions into cause for legal redress. If a Prime Minister can be investigated for being rude about Welsh people in the privacy of his home, it seems reasonable to assume that no one is safe from this kind of thing.

Notwithstanding T.’s kind suggestion, I shall go on worrying about the gradual elimination of free speech. The people who should be worrying about it on my behalf (politicians, legal profession, civil rights activists) are clearly falling down on the job.

• Reader M.W. asks, “Is it possible to be sarcastic about someone without being personal?” Yes it is, M., though the dividing line may be a little fine sometimes, and there is often a strong temptation to cross it.

Mediocracy likes to promote resentful belligerence towards other individuals as a form of self-assertion. Manners and self-restraint are examples of bourgeois fetishism and hence to be rejected ... Ultimately, ‘assertiveness’ is unavoidable for someone living in a mediocracy, as it becomes the only practical way of dealing with everyone else’s assertiveness. (Mediocracy, p.35)The key thing is to try to minimise attacking the person’s ego, particularly in sensitive areas such as appearance or personal life. Taking Tony Blair as a (currently) innocuous example, there is little risk of being offensive with sarcasm about the extent of his leftism or the absurdity of his professed ideology, however harsh the sarcasm. However, Mr Blair might reasonably feel unfairly slighted if one were to be rude about his hairstyle, his grin, his sexual prowess or his social antecedents. Such forms of attack should therefore be avoided, although they may be legitimate in the field of professional comedy.

Another criterion to apply is to consider how many indigenous defenders, particularly for the characteristic under attack, the victim would be able to call on. Mr Blair would no doubt be able to muster many supporters for his ideology, even now. On this basis, it could be regarded as less acceptable to sneer at (say) Gillian McKeith for being Gillian McKeith than to criticise someone for being a member of a religion with a national membership of over a million. “If McKeith didn’t want to be sneered at, she shouldn’t have agreed to go on a reality show.” This now seems to be a common attitude, and one applied not just to entertainers or would-be entertainers. “If people don’t want to be ridiculed about their hairstyle, dress sense, or whether they have sexual fantasies about former Prime Ministers, they shouldn’t become politicians.” If this principle is regarded as legitimate, what kind of person does that leave who is willing to accept it as a condition of exercising political power?

* * * * *

• Anecdote from my postgrad days

Fellow economics PhD student: “Hi, what are you doing?”

Me: “Er, thinking.”

She: “Oh yes, thinking. My supervisor said it was a good idea to set aside a certain amount of time for that.”

Her supervisor was one of the ‘top’ microeconomists in the world, but I doubt he meant what I mean by “thinking”. If he had, his student might have noticed that what she was writing for her thesis, and reading in aid of it, was so artificial and remote from reality that the chances of it leading to some genuine advance in understanding were zilch, and (if she had continued the train of thought) might have concluded that she ought to do something else.

* * * * *

A society broken by phoney ideology cannot be fixed without ideas that come from outside that ideology. Such ideas are unlikely to develop unless dissident intellectuals are supported.

Part 2 of Just another PC think tank will be published in 2011.

Part 2 of Just another PC think tank will be published in 2011.