Arts Council England is cutting funding to a significant proportion of the cultural organisations it has been supporting. On the execution list are, for example, the Bristol Old Vic and the City of London Sinfonia. Predictably, artists are complaining, while arts honcho Sir Brian McMaster seems positively orgasmic about the future prospects for British arts:

British society today is, I believe, the most exciting there has ever been. It has the potential to create the greatest art ever produced. We could even be on the verge of another Renaissance.

Phew. McMaster’s

report is clear about the

kind of culture which needs to be supported to fulfil this destiny. It demands that art be "exciting", "risky", less "superficial" and that it provide "lasting impact". (For how to interpret these noises, see

here.)

A shake-up is said to have been needed for some time. The new criterion for selection is supposed to be "excellence", allegedly a retreat from the previous overt political programme of egalitarianism (e.g. opera: bad, community art: good). However, given what is likely to be the predominant politics of those appointed to make the selections, I doubt whether the term excellence can be taken entirely at face value. In any case, "broadening of audience" is still explicitly on the agenda as a factor.

"Cutting government subsidies". Wouldn't most free-marketeers argue this is a good thing? Some are not so sure: Devil's Kitchen is understandably

concerned about cuts to the theatre, including the National Student Drama Foundation.

In theory, the most efficient outcome is supposed to be if the state doesn't intervene. But is it that simple? Not if we are dealing with a heavily distorted market to begin with. The

theory of the second-best tells us: moving from an imperfect market scenario

in the direction of perfect markets, but not all the way,

can make things worse.

It's not surprising if the reaction of some to cutting subsidies to the arts — many of which seem these days to be generating material that is either vacuous, ugly, or over-politicised — is

good riddance. And cutting

may be the best solution in this particular case, though I suspect this exercise, like most exercises initiated by New Labour, is really designed to achieve ideological objectives: some more destruction of bourgeois culture (classical music, traditional theatre) under cover of 'anti-elitism'.

However, the full story is not just about the market as we know it, because we don't really have a pure market, but rather a mixed economy which has been heavily engineered over the past sixty years to achieve downward redistribution, particularly with respect to capital and investment income.*

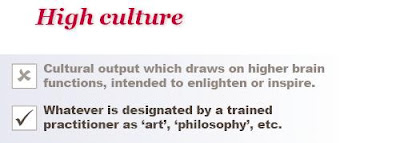

The

market as it is usually conceived these days means: buying and selling end products among a relatively homogenised salary-earning population. This partial version of the market can produce plenty of good culture, but it cannot easily produce cutting-edge high culture. It does not, by itself, produce novel theories in theoretical physics, or philosophy, or genuinely innovative theatre — though it may produce pop culture which trades under the 'iconoclastic' label, e.g. Mark Ravenhill's in-your-face plays, or Bernard-Henri Lévy's pseudo-radical chic. (

Baumol and Bowen have highlighted some other problems with cultural markets fuelled purely by consumption expenditure.)

Innovative high culture requires patronage. This can in theory come via the state, collected by forced subscription from taxpayers, but the evidence suggests that what this generates is severely limited on the good-culture side, and not nearly limited enough on the bad-culture side. That leaves private capital.

Private capital has few supporters these days. Inherited capital has even fewer. However, many of the cultural advances of the past would not have happened without it. I am fairly certain it would be possible to construct an economic model, based on genetic heritability, which purported to show that culture progressed best if inheritance was not taxed at all. I am equally certain such a model has not been published by an academic economist. (I am happy to be proved wrong on this, if someone has a reference.) The assumption of genetic transmission is considered so ideologically unsound that many economic papers now simply assume the opposite, i.e. no heritability, without even listing it as an assumption.

Two recent books on culture and capitalism, which otherwise have some interesting things to say, curiously avoid this crucial issue almost completely. In

Human Accomplishment, Charles Murray points to a correlation between cultural progress and capitalistic developments, but seems to prefer to attribute the link to

moral factors, boggling about the possible role of capital itself:

[...] whether wealth was a direct cause of Florence's artistic accomplishments or whether the wealth and artistic accomplishments were both effects of some other cause is difficult to entangle. (p.337)

Well, difficult if — like the academic historians whose work Murray accepts somewhat uncynically — you have an ideological resistance to seeing the obvious.

Tyler Cowen's

In Praise of Commercial Culture, while making a number of worthwhile points, also suffers from a mysterious lack of comment on the issue of capital inequality and cultural progress. Cowen rightly points out that

Parents and elderly relations have financed many an anti-establishment cultural revolution. Most of the leading French artists of the nineteenth century lived off family funds — usually generated by mercantilist activity — for at least part of their careers. (p.17)

But I did not come across anything in his book about how the decline in transmission of capital down the generations, as a result of stringent capital taxation, might have affected this, or about the related issue of how the changing character of the rich (fewer inherited, more self-made) has affected the top-level culture which gets produced. Perhaps because it has potential overtones of elitism, which would undermine Cowen's markets-are-good-for-the-people running theme. Very odd, however, given that the relationship between changes in what is called capitalism and changes in culture is — or should be — among the book's central concerns.

Bottom line. Genuinely free markets are perfectly capable** of generating innovative high culture. Economies in which capital and capital transfers are heavily taxed are not, at least not to the same degree. Should such economies have government subsidy instead? Probably not. What gets subsidised is more often than not whatever is considered correct at the time, so genuine potential innovations will be passed over. Should existing subsidies be cut? That is more difficult. Second-best theory says, you may make things worse. Some good things may be being subsidised, and if there is no private capital to step into the breach, culture will deteriorate. On the other hand, the subsidised activity, if not exactly bad, will tend to crowd out the more innovative culture which is bubbling under, waiting for private patronage. Such patronage is less likely to arrive if there is already an official high culture.

* I know inequality is supposed to have been increasing, but I don't buy the usual version of this theory. First, the measure is too crude: we need to look at the relative performance over time of individual classes, not just a single measure like the Gini coefficient, which is currently being distorted by a tiny minority of super-rich at the top. Second, nominal increases in income need to be deflated by reference to class-specific baskets (which they typically aren't), since inflation has been varying widely between different areas of expenditure. Third, some of the studies purporting to show increases are clearly based on nonsense data, since they look at pre-tax instead of post-tax incomes.

** As always, I wish to add the caveat that I don't believe the free market produces the best outcome, just the least bad. Culture has some public good characteristics: it is mostly non-rival, and is often unexcludable, so it will tend to generate market failures. However, the contemporary knee-jerk reaction to anything being less than perfect, which is to want to throw the state at the problem, should be resisted. Particularly in this case, because there is no reason to think that government agents, or those whom they appoint, will select (genuinely) progressive culture.

Brown and Blair are probably similar in terms of innate abilities. Their different levels of success in the public arena can be attributed partly to the differences in their schooling. State comprehensive schools, like the one Brown attended, purvey a mediocratic ethos. The individual is unimportant: he should regard himself as no better than anyone else, and as subordinated to society.

Brown and Blair are probably similar in terms of innate abilities. Their different levels of success in the public arena can be attributed partly to the differences in their schooling. State comprehensive schools, like the one Brown attended, purvey a mediocratic ethos. The individual is unimportant: he should regard himself as no better than anyone else, and as subordinated to society. The play Pornography, inspired by the 2005 London bombings and receiving its British premiere at this year's Edinburgh Festival, has received warm reviews in the Telegraph and the Guardian. According to its author Simon Stephens, the bombers

The play Pornography, inspired by the 2005 London bombings and receiving its British premiere at this year's Edinburgh Festival, has received warm reviews in the Telegraph and the Guardian. According to its author Simon Stephens, the bombers

The other entry for this year's Turner is Tomma Abts, whose work I quite like. (Yes, it's true — I don't hate all contemporary art.) Picture on right is Pabe, courtesy Gallery

The other entry for this year's Turner is Tomma Abts, whose work I quite like. (Yes, it's true — I don't hate all contemporary art.) Picture on right is Pabe, courtesy Gallery